post by Kathryn Antonelli, Project Manager for In Her Own Right

Have you ever heard the term “romantic friendship”? The term is used in historical scholarship to describe an intimately loving yet non-sexual (or perceived to be non-sexual) relationship between two non-related people of the same sex. Romantic friendships differ from platonic friendships in the intensity of the bond involved, and the inclusion of close physical affection and emotionally poetic communication. The aspect of communication is important because the term is used retrospectively; most of the documentation we have of romantic friendships is based on the contents of love letters and poetry, rather than studies or interviews that might more explicitly define the relationship.

Although they have existed throughout history, relationships of this type rose in popularity in the 17th and 18th centuries, and were looked upon tolerantly if not favorably throughout that period as well as throughout most of the 19th century. Scholars have proposed that romantic friendships became more common due to the extreme separation between women’s and men’s lives, both social and quotidian. Close relationships between women were romanticized by men as being intrinsically virtuous and pure, partially because most men did not believe sexual relations between women were possible—never mind desired. This meant that to a reasonably socially acceptable degree, women who were not married or did not wish to be married had an alternative, and women who were trapped in loveless marriages had an opportunity to be emotionally fulfilled.

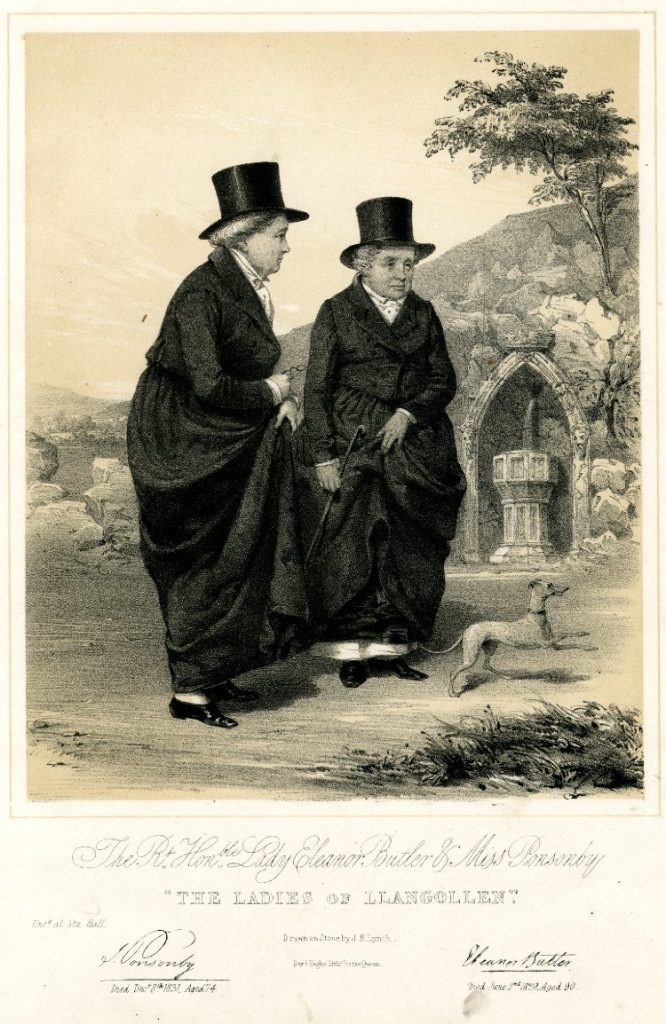

Photomechanical (from a lithograph) portrait of the Ladies of Llangollen. They left their respective lives behind to be together in Wales, and became one of the most well-known romantic friendships of their time. Courtesy of the British Museum – museum number 1932,0727.1.

The related term “Boston marriage” is sometimes used to describe instances of these relationships when the women lived together, especially in New England. Boston marriages reached the height of their popularity during the period 1870-1920, and were frequent among academic women. In fact, the more specific term “Wellesley marriage” was coined after the practice became common amongst the faculty at the all-female Wellesley College. Similar but less committed relationships, especially between female college students, were referred to as “smashes”, “crushes”, or “spoons”, and even involved complex courting rituals. Because women were often expected to resign from academic posts after marriage, many of these college women eventually decided to renounce all serious relationships with men, believing that their own careers and intellectual interests should take precedence in their lives. Some Wellesley marriages were therefore born out of financial convenience, but others formed based on serious relationships and attraction between the women.

English professor Katherine Lee Bates, who is most popularly known as the writer of “America the Beautiful”, published a book of poetry about her 25-year relationship with Katharine Coman. Bryn Mawr college president M. Carey Thomas openly discussed her “marriages” and the possibility of physical love between women. And, although it is mostly the lives of well-off white women that we are aware of today, there is evidence that lower class women and also women of color maintained similar relationships. The best known example is domestic servant Addie Brown and teacher of freed slaves Rebecca Primus, who wrote numerous letters to each other.

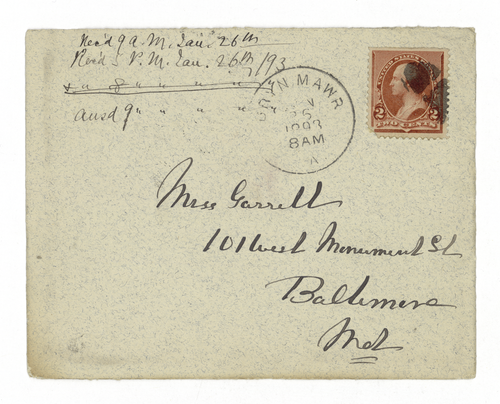

The envelope containing a letter from M. Carey Thomas to Mary Elizabeth Garrett dated January 25, 1893, courtesy of Bryn Mawr College and In Her Own Right. The two women wrote each other frequently, and eventually almost daily, until they began living together in 1904.

Slowly but surely at the turn of the 20th century, developments in the social sciences and sexology caused romantic friendships to begin to be looked upon as a potential danger to the institution of heterosexual marriage. Beginning in the 1920s, women living together were suspected of participating in “deviant behavior” and were shunned from polite society. Because of this shift, and because the terminology women at the time may have used to describe themselves cannot consistently be matched with modern labels, it is difficult to conclusively say whether any of the women in these relationships could be considered to fall under the modern umbrella of LGBT+.

Some scholars argue that we should not ascribe labels to people from the past who cannot confirm or deny them, while others decry the pervasive paradigm of compulsory heterosexuality that assumes all people from the past are straight until proven otherwise. Still others point to examples of romantic friendship-like relationships in our own age, or argue against the lines we have drawn between sexual, emotional, and romantic love altogether. In any case, the presence or absence of sexual behavior in these romantic friendships does not change the importance of the deep personal connections that they embodied. By studying letters, diaries, and other evidence that has been left behind (including that which In Her Own Right is endeavoring to collect), we can better understand how these women interacted—and how they conceptualized their own lives.

Ready to explore? Check out our collection guide for the M. Carey Thomas papers, and view digitized items in the In Her Own Right database.

Works cited/For further reading:

Faderman, Lillian. (1991). Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth-Century America. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Faderman, Lillian. (1999). To Believe in Women: What Lesbians Have Done for America - A History. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin.

Gibson, Michelle, & Meem, Deborah Townsend (Eds.). (2005). Lesbian academic couples. New York, NY: Harrington Park Press.

Moore, Lisa. (1992). "'Something More Tender Still than Friendship': Romantic Friendship in Early-Nineteenth-Century England." Feminist Studies, 18(3), 499-520.